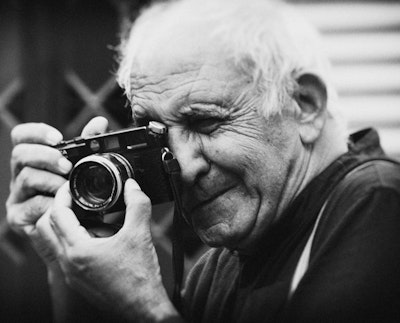

Uliano Lucas

Uliano Lucas, (Milano, 1942)

Nato a Milano nel 1942, Uliano Lucas cresce nel clima di ricostruzione civile e intellettuale che anima il capoluogo lombardo nel dopoguerra. Ancora diciassettenne, inizia a frequentare l’ambiente di artisti, fotografi e giornalisti che vivevano allora nel quartiere di Brera e qui decide di intraprendere la strada del fotogiornalismo.

I primi anni lo vedono fotografare le atmosfere della sua città, la vita e i volti degli scrittori e pittori suoi amici – Enrico Castellani e Arturo Vermi, Piero Manzoni e Nanda Vigo – ma anche raccontare i nuovi fermenti nella musica e nello spettacolo, dal Cab 64 di Velia e Tinin Mantegazza ai gruppi rock degli Stormy Six e dei Ribelli. Poi arriva il coinvolgimento nelle riflessioni politiche scaturite dal movimento antiautoritario del ’68 e l’impegno in una lunga campagna di documentazione sulle realtà e le contraddizioni del proprio tempo: l’immigrazione in Italia e all’estero, la distruzione del territorio legata all’industrializzazione, le proteste di piazza degli anni ’68-’75, il movimento dei capitani in Portogallo e le guerre di liberazione in Angola, Eritrea, Guinea Bissau, seguite con i giornalisti Bruno Crimi ed Edgardo Pellegrini per riviste come Tempo, Vie Nuove, Jeune Afrique e Koncret o per iniziative editoriali diventate poi un punto di riferimento per la riflessione terzomondista di quegli anni.

Uomo colto e visionario, Lucas lavora in quel giornalismo fatto di comuni passioni, forti amicizie e grandi slanci che negli anni ’60 e ’70 tenta di opporre una stampa d’inchiesta civile all’informazione consueta del tempo, poco attenta ad una valorizzazione della fotografia e imperniata sulle notizie di cronaca rosa e attualità politica. Collabora negli anni con testate come Il Mondo di Mario Pannunzio e poi di Arrigo Benedetti, Tempo, L’Espresso, L’Europeo, Vie nuove, La Stampa, il manifesto, Il Giorno, Rinascita, o ancora con Tempi moderni di Fabrizio Onofri, Abitare di Piera Pieroni, Se – Scienza e Esperienza di Giovanni Cesareo e con tanti giornali del sindacato e della sinistra extraparlamentare. A servizi sull’attualità e sul mondo dell’arte e della cultura, alterna reportage, che spesso sfociano in libri, su temi che segue lungo i decenni: dalle trasformazioni del mondo del lavoro, alla questione psichiatrica. Racconta le nuove forme d’impegno del volontariato degli anni ’80 e ’90, le iniziative del Ciai (Centro italiano per l’adozione internazionale) in India e in Corea e le realtà della cooperazione in Africa. Durante la guerra jugoslava vive e restituisce in immagini le tragiche condizioni di esistenza della popolazione sotto assedio.

Nei primi anni ’90 collabora intensamente con la rivista King, con il Corriere della Sera e il suo supplemento Sette ed è coinvolto da Guido Vergani nelle inchieste sulla Grande Milano delle pagine cittadine di Repubblica. Su questa testata pubblica diversi reportage sulle architetture e gli spazi di Milano e del suo infinito hinterland che si inseriscono in un lavoro mai interrotto sul cambiamento del territorio come specchio delle trasformazioni nell’economia e nel tessuto socio-culturale italiani.

La chiusura della maggior parte dei giornali con cui collabora e i cambiamenti nel sistema dell’informazione e della produzione e distribuzione della notizia, lo portano però a diradare le corrispondenze giornalistiche per dedicarsi a inchieste di ampio respiro condotte insieme a giornalisti, sociologici e storici. In esse Lucas interpreta il cambiamento epocale che si sta compiendo a cavallo del nuovo millennio attraverso una ricerca estetica influenzata anche dalle tendenze del linguaggio visivo degli ultimi anni. Fra il 1998 e il 2002 viaggia in Cina, raccontando il fermento di una paese che scopre un nuovo benessere e una nuova libertà, in quel momento di rapido e vorticoso passaggio che trasformerà questa nazione da paese “in via di sviluppo” in superpotenza. E poi continua a raccontare i diversi volti del proprio tempo: i cambiamenti nel mondo del lavoro in una società ormai postindustriale, le realtà dell’emigrazione tra accoglienza, integrazione ed emarginazione, il mondo giovanile con la sua cultura e la sua irrequietezza in un quadro socio-politico segnato dall’incertezza e dalla fine delle ideologie. Da un’intensa collaborazione dei primi anni 2000 con la rivista Io e il mio bambino ha origine un racconto ancora in gran parte inedito sulla nascita e la maternità. Del 2006 è il reportage sulle carceri di San Vittore e Bollate, realizzato per la Triennale di Milano con Franco Origoni e Aldo Bonomi; del 2008 il libro Scritto sull’acqua, in cui le sue immagini sulle popolazioni borana dell’Etiopia meridionale dialogano con il racconto letterario di Annalisa Vandelli. Nel 2016 con il libro Il tempo dei lavori, Lucas torna poi a indagare il mondo del lavoro a Genova a vent’anni dall’inchiesta Lavoro/lavori a Genova. Degli ultimi anni sono anche la lunga indagine sul territorio di Bari e il racconto sull’attività del centro per richiedenti asilo di Settimo Torinese, in cui Lucas rinnova, con uno stile che riflette i cambiamenti del tempo, l’impegno di conoscenza e analisi e la capacità narrativa ed evocativa che lo hanno da sempre contraddistinto.

Tatiana Agliani

English

Uliano Lucas was born in Milan in 1942 from a labour family. He grew up during the civil and intellectual reconstruction that characterized Lombardy during the post-world war. He carried out his studies in renaissance boarding schools where teachers such as Luciano Raimondi, Albe Steiner or Guido Petter supported partisan children offering them the possibility to study.

17 year old Uliano was expelled from school as he was too undisciplined: curious and restless when he started to mix with artists, photographers, and journalists who all lived within the area of Brera. During his endless discussions with graphic designers, intellectuals and artisans of the old Milan-at Genis or Giamaica bars- as well as talking to the photographers Ugo Mulas, Mario Dondero and Alfa Castaldi, he decided to attempt photo-journalism. At this point, Uliano saw in photo-journalism a mean of civil commitment as well as an independent profession, free from constraint, the encouragement to discover different worlds later characterizing his whole existence.

During the beginning of his career he depicts working-class moments of his town, i.e. the life and presence of his fellow writers and painters – Enrico Castellani, Costantino Guenzi, Piero Manzoni and Arturo Vermi. He also draws a picture of musical and theatrical excitement: going from Tinin Mantegazza’s “Cab ’64” to rock groups such as Stormy Six and Ribelli.

Later he becomes involved in political movements stirred by the new Italy of the 60s and his commitment towards a long campaign that documents historical processes at the basis of a cultural debate of his time: immigration in Italy and abroad, the destruction of the territory due to industrialization, the student and antiauthoritarian movement throughout Europe and Italy with its street protests during the years ’68-’75; the movement of captains in Portugal and the wars for liberation in Angola, Eritrea and Bissau Guinea. Uliano documents these themes with his fellow journalists Bruno Crimi and Edgardo Pellegrini for magazines such as Tempo, Vie nuove, Juene Afrique and Koncret or for editorial initiatives that later became a reference point for the third world reflections during those years.

During the 60s and 70s, Uliano Lucas, cultural and visionary man, is part of that journalism based on common passion, strong friendship, and deep impulse that tries to oppose the usual information of that time (characterized by a lack of enhancement for photography but attentive towards the gossip column and political events) with a civil inquiry press. He interacts with directors and managing editors such as Nicola Cattedra, Gianluigi Melega, Pasquale Prunas, Giovanni Valentini, Tino Azzini, Nini Briglia, Giovanni Raboni and Anna Masucci. He also speaks to journalists, graphic designers and photographers committed like him to a thorough enquiry of Italy. Together with the above mentioned, Uliano gives life to reportage, exhibitions, editorial projects such as Azimut (trade-union magazine), the periodical Illustrazione Italiana or the Idea Editions series ” The fact, the photograph”. His style is typical of those who depict indignation towards abuse and social inequalities. He is convinced of the importance of journalism as a democratic mean for information that combines both a harsh denunciation and documented evidence of facts with an attentive eye with regards to humanity for the people depicted, their personal stories of grief or just simply their lives.

Uliano Lucas collaborates with newspapers such as Mario Pannunzio’s Il Mondo (that then became Arrigo Benedetti’s), with L’Espresso, L’Europeo, Vie nuove (that then became Giorni-Vie nuove), La Stampa, il manifesto, Il Giorno or again with Fabrizio Onofri’s Tempi Moderni, Piera Pieroni’s Abitare, Giovanni Cesareo’s SE Scienza Esperienza. He collaborates with many trade union and left wing extra-parliamentary newspapers. He undertakes jobs regarding current events, art and culture in general (of which he has always been an attentive observer) and reportage (that often are transformed into books) depicting transformations within the job world, to better understand the state of the country. Uliano alternates the above tasks with a close analysis of the mental disorder matter of which he makes large documentation: high-lighting its slow transformation from mental homes in the 70s to the acquisition of freedom and normal life during the 80s and 90s. He also works for Tempo, during which period he travels throughout Spain and Portugal: his expression of the asphyxial dictatorship is clearly stated. In 1982 he works for L’Espresso and depicts Israeli and Moroccan writers; during the same period, he is also a correspondent in Sicily, Puglia, Calabria on mafia matters. When working for L’Europeo, he documents the disaster at Seveso and describes the many aspects of the catholic world. Uliano collaborates with L’Exspress, Le Nouvel Observateur, Time thanks to Grazia Neri, and produces works on current events, politics and custom.

Gradually, he talks about the new commitment of voluntary service in the 80s and 90s, the initiatives of Ciai in India and Corea and cooperation in Africa. During the war in Yugoslavia Uliano provides pictures of the tragic conditions of local population in state of siege.

The closing down of large part of the newspapers he collaborated with between the 80s and 90s and changes in the system of information and distribution of the news, bring him to slow down, in these last 15 years; but he dedicates himself to the study and research of photography which has always accompanied his profession as a reporter. He also turns to broad surveys conducted with journalists with sociological and historical experience: an example of which is the story of the early 90s regarding recovery centres for drug-addicts in Turin, (carried out with Carlo De Giacomi); the documentation of the same years on the hard industrial conversion in western Genoa (done with Leila Maiocco and the trade unionist Franco Sartori) or the recent report on prisons such as San Vittore and Bollate, (created for the Milan Triennale with Franco Origoni, Marella Santangelo and Aldo Bonomi) and the survey on the life of the boron population of southern Ethiopia (executed with Annalisa Vandelli).

However during the beginning of the 90s he works intensively for the King magazine and for Il Corriere della Sera and its supplement Sette. From 1989 to 1995 he is involved with Guido Vergani e Paolo Mereghetti in inquiries regarding the Great Milan city pages of la Repubblica. Subtle interpreter as well as punctual witness of more than forty years of history, he publishes on this newspaper many of those shots made in a daily reconnaissance on the territory which offer a comprehensive story on Italian society for the 80s and 90s and for the new Millennium, (as it had occurred for the 60s and 70s), also showing a new style with regards to radical changes of mentality, custom and traditions. He produces reports on architectures and spaces of Milan and its infinite hinterland that fit into a never-ending work by Lucas on the changes within the territory as a mirror of the transformations in the economy and in the socio-cultural fabric documented by him since the 60s all over Italy. This work renews his commitment to knowledge and to analysis and confirms his narrative and evocative skills which have always distinguished him.